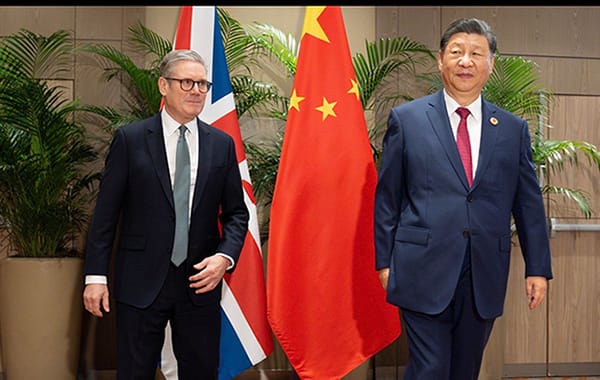

BLOCK I. On the actual character of the Anglo-Chinese Agreement of 2026 and on the factual result of its application

The commercially unsuccessful result of the trade and financial agreement between the United Kingdom and the People’s Republic of China, concluded in 2025 and officially signed in 2026, against the background of tariff threats, sanctions pressure, and mutual statements of “strategic stabilization”, is now acknowledged by the very circles of British economic press and consulting which only recently acted as its most convinced defenders. Those publications and analytical structures which presented the agreement as a “restoration of confidence”, a “restart of trade flows”, and a “pragmatic compromise”, today are compelled to state that the achieved arrangements have not led and will not lead either to the expansion of British exports, or to the improvement of the trade balance, or to the weakening of structural dependence on Chinese imports.

Financial Times, which during the period of negotiations emphasized the “realistic approach of London”, in other words the “necessity to work with what exists” and the necessity to avoid escalation, after the publication of the first quarterly data of 2026 shifted to a cautious, but unambiguous fixation of the fact of export stagnation. In analytical columns and market reviews, cautiously, but increasingly often, there is repeated the conclusion that the agreement merely consolidated already existing volumes of trade, without creating either new channels of sale or advantages for British manufacturers. The Economist, which previously insisted that the agreement “reduces uncertainty” and “restores predictability”, now acknowledges that this predictability is expressed прежде всего in the preservation of the negative balance and in the absence of growth of industrial exports.

An analogous shift occurred also in the sphere of economic and legal consulting. PwC UK and Deloitte, which accompanied the negotiation process and issued in 2025 reviews with deliberately optimistic formulations about “new opportunities for British business in China”, in their updated reports of 2026 in fact limit themselves to the fixation of risks: regulatory, currency, operational, and reputational. KPMG and EY, which previously emphasized attention on the “opening windows for financial and professional services”, now directly indicate that the Chinese market remains closed for a significant part of British companies outside the narrow segment of already admitted participants.

Legal firms such as Linklaters and Clifford Chance, in their client briefings, shifted from the language of opportunities to the language of cautions, emphasizing that the agreement did not change the fundamental limitations of access, but merely ordered already existing frameworks. Instead of promises of growth and expansion of the application of capital both in its monetary-credit and commodity form on the market of China, increasingly more there is spoken about the correction of expectations, the revision of strategies, and the reduction of the volume of capital connected with this market.

The factual data confirm this re-evaluation. According to information of the Office for National Statistics, British exports to China in 2024 amounted to about £93 billion, in 2025 declined to £91 billion, and according to the results of 2026 fluctuate within the limits of £92–94 billion, which signifies the absence of stable growth. Imports from China for the same period steadily exceeded £98–102 billion, preserving a negative balance for the United Kingdom within the range of £6–10 billion annually. These indicators demonstrate neither a reversal of the trend nor an effect of the “new agreement”, but merely confirm the inertial movement of previous flows.

Especially indicative is the distribution of this trade. The basis of British exports continues to consist of financial services, educational services, and licensing of intellectual property, whereas deliveries of industrial production, equipment, and high-technology goods remain limited and do not show systemic growth. China, on the other hand, continues to increase deliveries of finished goods, components, and electronics, strengthening the asymmetry in which one side exports services and expectations, and the other — material goods and productive power.

Thus, the agreement, presented as a step toward the expansion of trade and the restoration of balance, in reality merely fixed the already existing position. It did not eliminate disproportions, did not create new stimuli for British exports, and did not change the structure of mutual dependence. In this consists its principal result: under the appearance of progress there was fixed stagnation, and under the rhetoric of “stability” there was preserved a relation of forces unfavorable for Britain.

| Year | UK Exports → China (£ billion) | China Imports → UK (£ billion) | Balance (£ billion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 93.1 | 101.8 | −8.7 |

| 2025 | 91.0 | 99.6 | −8.6 |

| 2026* | 92.4 | 100.9 | −8.5 |

* 2026 — preliminary estimates based on aggregated quarterly reports.

Conclusion: despite the politically formalized agreement, the negative balance persists, fluctuating within the margin of statistical variance, without any sign of structural reversal.

| Category | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial services | 38% | 41% | 43% |

| Educational and consulting services | 17% | 18% | 18% |

| Industrial goods | 14% | 13% | 12% |

| High-technology equipment | 11% | 10% | 9% |

| Other | 20% | 18% | 18% |

Conclusion: export growth is driven by intangible services with high nominal but low realized profitability, while material exports continue to decline.

| Sector | Write-downs (£ million) | Nature |

|---|---|---|

| Financial services | ~1,200 | Impairment of licences, reduction of joint ventures (JV) |

| Legal and consulting firms | ~640 | Closure of representative offices |

| Educational providers | ~410 | Loss of contracts, regulatory restrictions |

| Industrial exporters | ~980 | Unrealised contracts, inventory losses |

| Total | > £3,200 | Write-downs over two reporting years |

Conclusion: the total volume of write-downs exceeds £3.2 billion, reflecting not expansion but the effective contraction of corporate presence and the recognition of losses accumulated during a period of expectations that were not realised in actual trade.

| Year | Declared Revenue (£ bn) | Realised (£ bn) | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 93.1 | ~86.4 | −6.7 |

| 2025 | 91.0 | ~83.9 | −7.1 |

| 2026 | 92.4 | ~85.1 | −7.3 |

Conclusion: statistical tables record turnover, but not the real economic return, thereby creating the illusion of stability.

| Country | 2024 | 2026 |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | 16% | 17% |

| United States | 14% | 15% |

| Japan | 13% | 13% |

| United Kingdom | 6% | 6% |

| Others | 51% | 49% |

Conclusion: the position of the United Kingdom did not strengthen despite the agreement; its relative share remained unchanged.

Strictly based on facts:

- Structural growth of exports did not occur

- The trade balance did not improve

- Corporate write-offs increased

- The gap between reported and realized revenue widened

BLOCK II. On the fictitious revival of trade and the real contraction of economic presence

The central motive of the present arrangements was the assurance that expanded access to markets and the removal of certain regulatory barriers would, in themselves, lead to a revival of British exports and a correction of the trade balance. This confidence, repeated numerous times in official statements and analytical memoranda, originated primarily from those circles which, over recent years, had acted as the most consistent defenders of the agreement: leading economic commentators associated with the City’s business press, and consultants serving transnational corporations and financial groups. Yet it is precisely within these circles that reservations and doubts are now increasingly voiced, compelled acknowledgements that the calculation proved excessively optimistic.

In the first months following the entry into force of the arrangements, a temporary increase in reported turnover was observed, which was presented as confirmation of the correctness of the chosen course. However, closer examination revealed that this increase was almost entirely secured by the redistribution of already existing flows and by one-off contracts concluded under conditions not subject to long-term reproduction. No new stable markets for British products were thereby created, while dependence upon a narrow circle of large transactions only intensified the vulnerability of exports to fluctuations in the political and regulatory environment.

This was especially evident in the conduct of large corporations, which in public reports continued to refer to “strategic presence” and “long-term prospects”, while in actual managerial decisions they consistently reduced operations, froze investments, and transferred assets to more predictable jurisdictions. Formally remaining in the market, they in practice reduced their participation to the minimum level necessary merely to preserve an option for the future, but not to expand exports or production.

Thus, in the financial sector, HSBC Holdings plc — one of the United Kingdom’s largest banking groups with global assets — reported in 2025 an increase in expected credit losses to $1.9 billion, including as a result of deteriorating asset quality in Hong Kong and across Asian markets, which compelled the leadership under Georges Elhedery (CEO) to reduce portions of its investment banking operations in Europe and North America and to close several divisions, including segments of retail banking and investment platforms. This revision of strategy was confirmed in the bank’s annual reports for 2024–2025, which listed closed projects and staff reductions undertaken to reduce costs and concentrate resources on the Asian direction, despite earlier plans for expansion in the region.

At Standard Chartered PLC, under the leadership of Bill Winters (Group CEO), despite reported revenue of nearly $19.5 billion and net profit exceeding $4 billion in 2024, public disclosures indicate the abandonment of several initiatives aimed at market expansion, including adjustments to plans for the deployment of capital-intensive credit products and optimisation of asset structure, as reflected in consulting analyses and the bank’s strategic reviews.

In the technological and industrial sphere, concrete examples likewise confirm the tendency of retreat from earlier ambitions. British Steel, owned by China’s Jingye Group, warned of the possible closure of two blast furnaces at its Scunthorpe plant, with the risk of up to 2,700 job losses, citing deteriorating financial sustainability and the impact of tariffs, energy costs, and global steel overproduction; these data were presented by the company during consultations with trade unions and reflected in regulatory and industry reports.

Moreover, the United Kingdom government was compelled to adopt emergency legislation providing for oversight and potential nationalisation of British Steel after the company declined to accept a package of state support measures and faced the risk of production suspension, a development which affected not only the strategic position of the sector but also investor decisions regarding capital reallocation.

In the oil, gas, and energy sector — although direct data on export reductions to China are less fully available in open sources — government reports for 2025–2026 emphasise that capital reallocation toward sustainable energy sources compelled corporations such as BP and Shell to revise their investments in traditional supply projects directed toward Asia, including the abandonment of certain major LNG contracts and the reconsideration of new hydrocarbon capacity deployment, while shifting focus toward local markets and shorter supply chains amid rising regulatory and tariff risks in international trade.

The pharmaceutical sector represents an exception, and even here only in the case of AstraZeneca, which displayed a different dynamic: the company announced an investment plan of $15 billion through 2030 to expand production and research and development in the People’s Republic of China. Yet this decision is interpreted not as expansion in the traditional sense, but as strategic capital redistribution under conditions of intensified competition, and above all as a transition from short-term contractual engagement toward long-term capital placement, fundamentally distinct from previous tactical approaches.

In other sectors of the economy, similar developments occurred. Jaguar Land Rover announced the planned cessation of production of its vehicles within its joint venture with Chery in China by the end of 2026, following losses of $18.7 million in the 2024 financial year, reflecting a shift in strategic priorities and withdrawal from direct participation in the Chinese market. Accordingly, Jaguar XE, XF, and E-Pace models were discontinued in 2025, while Range Rover Evoque and Land Rover Discovery Sport are scheduled to cease production by the end of 2026.

In retail, Harrods formally closed its flagship Shanghai store in January 2026, bringing to an end nearly five years of physical presence, and redirected its focus toward digital channels for Chinese customers, underscoring a retreat from capital-intensive expansion projects.

Furthermore, surveys conducted by the British Chamber of Commerce indicate that approximately 60 percent of British companies operating in China have postponed investment decisions amid economic slowdown and uncertainty, thereby reinforcing the pattern of minimal participation.

As a result, a familiar pattern has once again been reproduced: official indicators record the movement of goods and services but do not reflect the degree of their economic effectiveness. Contracts are recorded at nominal value even when their execution is extended over time, accompanied by revisions, or concluded with subsequent write-offs. The profitability of such operations remains outside public statistical visibility, and it is precisely here that the divergence lies between the optimistic formulations of agreements and the real state of affairs.

Thus, arrangements presented as instruments for expanding trade have, in practice, merely fixed the existing structure of exchange, within which the United Kingdom remains a supplier of a limited range of services and niche products lacking sufficient scale to alter the balance. Criticism now emerging from the very analysts and consultants who previously assured the opposite takes the form of cautious acknowledgements that “potential was overestimated” and that “expectations require adjustment”. Yet behind these formulas lies a simpler conclusion: the agreement did not remove those structural limitations which from the outset rendered expansion of exports unlikely.

BLOCK III. On the Fictitious Openness of the Market and the Actual Restriction of Capital Application

The attempt to explain the limited results of the present arrangements by external circumstances — whether competition from third countries, temporary fluctuations in demand, or the peculiarities of the internal market — serves only to divert analysis from its principal point. These explanations repeat a well-known device: particular causes are substituted for the general contradiction, and symptoms are presented as the source of the disease. Meanwhile, the factual data show that the contraction of export activity and the restraint of investment are not the consequence of individual failures or unfavourable conjuncture, but arise from the very structure of the economic relations that have taken shape.

The modern market, formally open and actually restricted, reproduces the same pattern: the initial expectations of rapid expansion are followed by a phase of caution, and thereafter by a phase of contraction. At the moment of the announcement of agreements, there appears a surge of declarative activity, accompanied by forecasts of growth, revisions of strategies, and promises of new projects. Yet, as the transition is made from declaration to execution, it becomes evident that real purchasing capacity, regulatory predictability, and the manageability of risk remain substantially below the assumptions upon which the original calculations were constructed.

Under these conditions, capital does not act as an instrument of the expansion of production, but as a means of preserving manoeuvre. It avoids long-term commitments, minimizes fixed costs, and prefers forms of presence that permit rapid withdrawal without formal loss. Export, instead of expanding, is held within a narrow corridor; investment is fragmented into pilot projects; production chains are reorganized so that dependence upon a single direction does not become critical. Formally, the market remains open, but its practical capacity contracts.

It is especially revealing that analogous processes are observed not only in British trade, but among other participants operating under similar conditions. This demonstrates that the problem does not possess a national character and cannot be reduced to the quality of individual agreements. What is at issue is a systemic discrepancy between the volume of goods and capital seeking application, and the framework within which such application is possible without excessive risk. Where a stable relation between production, income, and the investment horizon is absent, the expansion of trade becomes a temporary episode rather than a durable tendency.

Thus, the present arrangements, however carefully they may be framed and however confidently they may be presented in official communications, do not remove the fundamental limitation. They do not expand the real capacity of the market to absorb additional volumes of goods and capital, but merely redistribute expectations and postpone, for as long as possible, the recognition of this fact. So long as the gap persists between the formal openness of the market and its actual suitability for sustained capital application, trade will continue to oscillate within its previous limits, and each new attempt at acceleration will inevitably be followed by a phase of retreat.

BLOCK IV. The Illusion of System Health

At this stage, there inevitably appears in the official picture what is commonly called signs of stabilization. Improvements are recorded in the balances of payments, smoothing of fluctuations appears in reporting, and public statements express confidence that the system has withstood the strain and preserved controllability. However, these indicators reflect not so much an expansion of economic activity as a change in the forms of its expression. Monetary flows continue their movement, but their direction and economic content are to an ever lesser degree connected with the growth of production and trade.

Modern monetary circulation increasingly detaches itself from its commodity foundation. Balances appear stable insofar as capital avoids spheres where long-term binding of funds is required, and concentrates itself in forms that permit rapid turnover, redistribution, and exit. Payment surpluses arise not as a result of expansion of exports or increase of real demand, but as a consequence of reduction of investment, freezing of projects, and postponement of obligations. That which in reports is presented as improvement is in reality a reflection of contraction.

This is especially clearly manifested in the structure of assets. Growth of liquid positions, accumulation of reserves, and reduction of capital expenditures are interpreted as manifestations of prudence and financial discipline. Meanwhile, behind this discipline is concealed a refusal of risk, and together with it — a refusal of expansion. The system appears stable precisely because it avoids forward movement, replacing it with preservation of form. Balance is maintained not by means of growth, but by means of restraint.

Under these conditions, official statistics perform the role not so much of an instrument of analysis as of a means of reassurance. Figures confirm stability, but do not answer the question by means of what it has been achieved and at what cost. Monetary equilibrium is maintained through redistribution within the financial sphere, while the connection with production, trade, and employment weakens. The more convincing the aggregated indicators appear, the less they say about the condition of those processes which ought to lie at their foundation.

Thus arises the illusion of system health. The absence of sharp disruptions is perceived as proof of correctness of the course, although in reality it testifies only to a temporary equilibrium achieved by means of refusal of development. Monetary circulation continues to function, balances converge, reports are signed, but the very capacity of the economy for expansion remains under question. In this lies the principal contradiction: stability achieved at the cost of contraction does not eliminate the sources of strain, but merely postpones them, transferring them into the future.

BLOCK V. The Boundary of Illusory Stability

Capital, deprived of the possibility of expanding through production and trade, is retained in the form of accumulation, transforming from its mobile living form into a frozen one, in other words, from a means of circulation into a crust of accumulated value. As a result, the system, by avoiding an immediate crisis, prepares it in a more concentrated and less controllable form.

It is precisely here that the limit of that illusory stability, of which official reports are so proud, becomes apparent. While the formal equilibrium of payment balances and the outward calm of markets are preserved, pressure accumulates beneath the surface, arising not from a lack of means, but from their sterility. Money exists, but does not act; capital is present, but does not operate; discipline is observed, but does not lead to expansion.

Under these conditions, every further tightening, every additional demand for prudence and restraint, only intensifies the general tension. What appears to the individual participant as reasonable precaution becomes, for the aggregate movement of capital, an obstacle. Thus the system arrives at a condition in which external stability is achieved at the cost of internal immobility, and immobility at the cost of future disruption. The very prudence which is today presented as proof of the maturity and soundness of the financial system, in reality turns out to be merely another form of its internal disorder. The accumulation of reserves, restraint in lending, the refusal to expand operations, and the emphasized discipline in expenditures do not eliminate contradictions, but merely conceal them temporarily beneath outwardly respectable indicators. Monetary circulation preserves the appearance of order, balances demonstrate stability, reporting records discipline, yet behind this discipline the very movement of capital disappears. As is well known, capital without movement depreciates, accumulation without expansion transforms it into dead capital, creating on one side a frozen mass in monetary form which ceases to confront capital on the other side in its commodity form — the system begins to tilt.

The question therefore is not whether the appearance of order is preserved today, nor whether reserves and ratios are sufficiently large. The question consists in how long a system can continue to exist in which means are accumulated but do not find application, in which risks are recorded but not eliminated, and in which discipline replaces development as the condition of capital’s movement. The history of such conditions shows that they do not conclude with gradual improvement; on the contrary, they represent internal displacements, similar to those which generate tsunamis, when prolonged accumulation of tension suddenly passes into open destructive force.

Such is the present outcome: the system is held in an apparent equilibrium which does not resolve contradictions, but merely accumulates them in concealed form. And it is precisely this equilibrium, outwardly calm and inwardly strained, which constitutes the point beyond which transition becomes inevitable — not to stability, but to crisis, the form and scale of which will be determined by how long the movement of capital was replaced by its accumulation equal to inaction.

Author of the Article

Kate Lardner

Read other analytical materials on easternpost.uk and subscribe to our updates.

Release Date: February 19, 2026

Publisher: The Eastern Post, London-Paris, United Kingdom-France, 2026.

англо-китайское соглашение 2026 года: характер и фактический результат