China owns Britain. Britain owns China. America owns them both.

(Eastern Post – London, October 2025)

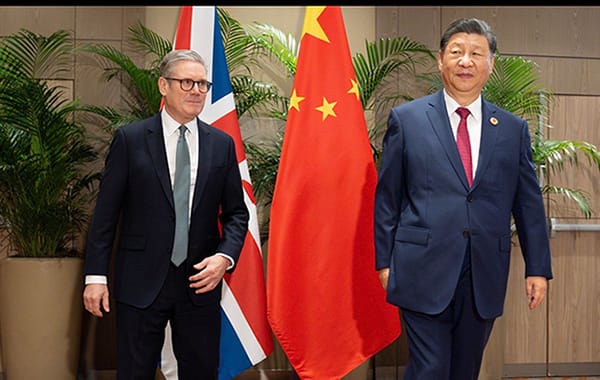

Facts are stubborn things. The Sunday Times China List reports (25 October 2025, The Sunday Times): structures linked to the Communist Party of China own 442 assets in the United Kingdom worth £190 billion, including nuclear facilities, water, gas, ports, schools, and even hotels for refugees, earning from contracts with the British state at least £15 million per year. This is not a hypothesis, but accounting. This is not diplomacy, but property. This is not friendship, but power, the author asserts.

But everyone who has eyes to see and ears to hear will understand that China is not buying Britain. Britain has put itself up for sale. And the further it goes, the clearer this deal looks: a country that once drew the map of the world with the ruler of empire now discovers that the main colour of its capital is not blue, but Chinese red. More than £190 billion in companies and property of the United Kingdom — from nuclear reactors to private schools — have smoothly and quietly shifted under the control of Beijing or those acting in its interests. This is what globalisation looks like when viewed from the seemingly favourable side of Chinese accounting.

Numbers speak louder than politicians.

In 2021, Chinese assets in Britain were valued at £134 billion. In 2023 — £152 billion. Today — already £190 billion. An increase of £56 billion in just two years — supposedly a “random” result of the free market. But most of this market is infrastructure, on which the very life of the British state depends. £51.3 billion of national assets are officially registered to structures connected with the Chinese state apparatus. Heathrow Airport — almost 9% in the hands of the Chinese sovereign fund. Thames Water and Cadent Gas — another £3.1 billion of control over British water and gas. Hinkley Point C — the future of the country’s nuclear energy — is one quarter owned by companies directly linked to the government of the PRC, their stake valued at £13.2 billion.

Where imperial taxes used to flow, now rent flows to Beijing. London office towers — “Cheesegrater”, “Walkie Talkie” — send their owners from Hong Kong £42 million and £46 million a year respectively. The Royal Mint — a historical symbol of British sovereignty — is now just an expensive plot of land for a planned new Chinese embassy.

But the most unexpected thing is the hotels for refugees. Holiday Inn in Warrington and Ashford, as well as Campanile in Cardiff, receive money not only from the UK Home Office, but also from the Chinese state companies that own them. At least £15 million per year — profit from the migration crisis in Europe itself. The British taxpayer pays for Beijing’s policy twice: first in shops — for Chinese goods, then in the budget — for the Chinese owners of British hotels.

Critics speak of “soft power.” But an inspection of the accounting shows power that is entirely material: £92.4 billion in FTSE company shares, including Shell, BP, Rio Tinto, AstraZeneca. China participates in shaping prices and the fate of British industry not through diplomatic notes, but through ownership.

If Great Britain once imposed rules on the world through trade monopolies, now the world imposes rules on Great Britain — through ownership of its assets. London proudly speaks of the principles of the free market, but the free market today looks like a market where British principles are being sold.

None of these deals is called a “defeat,” but each of them means a loss of leverage. Whoever owns energy, water, ports, real estate, and communications — owns the future of the country. For many years Britain has said that power must be divided. China calmly showed that power can simply be bought.

And yet the story of steel looks the most symbolic — the very steel that once formed the basis of British greatness. British Steel, the key producer of rails and major metal products in the country, came under the control of the Jingye industrial group from Beijing. The deal saved three thousand jobs — so they said. Did it save them? The question remains rhetorical: in government circles they seriously discuss whether the new owner is conducting a slow suffocation policy, to bind Britain even more tightly to Chinese imports.

When the government is forced to pass a law to keep the furnaces running at its own factories — this is no longer economic statistics, but a condition of the state. If metal is the skeleton of the economy, then its X-ray today shows many fractures. London calls this “mutually beneficial partnership.”

An important nuance: most of the investments from China are not private money seeking profit. They are the hands of one centre. Companies are obliged to fulfil the will of the state if the state calls. The law is written that way. It works quietly, but absolutely clearly. Owning infrastructure is owning levers. Levers do not lose strength because they are held in foreign hands — smiling.

Even school — a subject of pride for British society — has become an object of strategic interest. 28 independent educational institutions, where the elite learned to command the world, now teach children of those who will run Britain differently. The introduction of VAT on private education only made the path easier for foreign investors: a weakened organism is always easier to capture.

In Parliament, they speak of “complex relations,” of a “balance of interests.” In intelligence reports, they speak more clearly: trade with China has ceased to be neutral. It has become a space of struggle over norms, technologies, values. But to say this out loud means to admit that over the past twenty years, strategic control was not lost, but sold.

Someone calls Chinese expansion a threat. But a threat presupposes an explicit enemy. Here everything is more subtle: Britain itself signs the agreements, itself seeks capital, itself convinces itself that money is the best diplomat. Until it turns out that this diplomat works under the instructions of another state.

This is not a seizure. This is a lease of the future. With all the rights to endless extension.

If Britain once dictated world rules through a fleet, then today rules are dictated by the fleets of payments directed to Beijing. Sovereignty has ceased to depend on the number of ships. It depends on who receives the dividends.

China does not hurry, China does not pressure, China buys time. And time in the economy is worth more than any Haldane House and higher than any skyscraper in the City. China does only one thing: calmly and consistently turns British assets into sources of its profit.

And yet the most surprising thing in all this is not the scale of China’s presence, but the calmness with which it is accepted. When utilities — water, gas, heat — become investment instruments of a foreign state, it means not just income, but influence on the life of every home. 9% of Thames Water and 10.5% of Cadent Gas — shares that did not appear in public debates, because numbers do not need noise to change reality.

In green energy — the future artery of the economy — the picture is the same. The Inch Cape wind farm is valued at £1.75 billion, and half of this future wind belongs to the Chinese SDIC. At least seven more wind farms in England and Scotland are partly controlled by structures of Beijing. The burden of the technological transition to “clean energy” is borne by British families — the profit from this transition goes to Beijing.

In the digital sphere, dominance looks even quieter. The Global Switch data centres store data that Britons are used to considering their own. 60% of Logicor controls electronic supply chains. Hikvision surveillance — cameras that watch the streets — belong to those who look at the world differently. The threat here is not in the microchips. The threat is in the invisible geography of owners.

They say money has no nationality. But the capital directed by sovereign funds has the strictest nationality. £92 billion in FTSE-100 shares in the hands of investors from China and Hong Kong — a figure analysts call understated: 300 London Stock Exchange companies, including nine from FTSE-100, are not required to disclose their ownership lists. Transparency is apparently a product sold only in front of the cashier.

Even sports and culture — the arteries of public identity — have long been inscribed into Chinese portfolios. Polaroid, Clarks, Lotus Cars, Wolverhampton Wanderers. When fans sing the anthems of clubs managed from offices thousands of kilometers away, the phrase “home game” loses its literal meaning.

Economists insist that the United Kingdom receives “capital inflows.” And this is true. Capital inflow, as written in reports. But inflow, as is known, always turns into outflow — in the form of interest, dividends, and rent. The owner receives more than they invested. And whoever owns — writes the future.

In politics there is the illusion of choice. In economics, the choice is always made by the one who pays the bill. Today billions of pounds in profits — from energy networks to university campuses — are transferred to the accounts of organizations that are subordinated to political decisions of another state. This is not a scandal and not a conspiracy. This is just business.

And business is power, only without ceremonies.

One can speak of partnership, one can speak of mutual benefit. But when a country gives away not only money, but also the tools by which this money is earned — it gives away the ability to determine its own tomorrow. The United Kingdom loves to reason about sovereignty as a political right. China views sovereignty as an economic fact.

That is why while some countries argue about how to protect independence, others simply buy those parts of the economy that ensure this independence.

China does not ask questions.

China buys answers.

And Britain itself put them up for sale.

But, like any coin, there is a reverse side! And here it is:

British capital does not wave a flag over Chinese factories. It acts silently. Patents for equipment, licenses for software, legal support for export transactions, insurance of shipments and clearing of revenue — pass through structures subordinate to the world financial oligarchy, whose centers are located in London and New York. Every shift in Sichuan is paid for not by a workers’ council decision, but by the profit norm approved in the City. China builds production capacity, but builds it within rules defined not in Beijing, but on Walbrook.

On paper, direct British investments in the PRC look modest. However, control over the sectors responsible for the reproduction of value operates through channels of transnational capital: more than sixty percent of external operations in yuan are cleared through London. Insurance of Chinese export shipments to global markets is carried out predominantly through British institutions. Legal ownership of key technological and financial standards belongs not to the Chinese state, but to shareholders of corporations for whom the national flag is merely an accessory.

In metallurgy, where China produces more than half of the world’s steel, foreign holdings control critical nodes: automation systems, purification, blast-furnace equipment. Britain receives rent, comparable to colonial-era revenues, without owning mines and ports. It owns accounting norms and insurance coefficients. Even two to three percent from every ton of exported steel, flowing into London’s financial houses, expresses the fact that world markets belong not to those who produce the goods, but to those who control the circulation of value.

The digital economy is arranged the same way. China demonstrates technological power, but data clouds, service payment hubs, licensing of processors and communication protocols distribute dividends in favor of funds registered in British jurisdiction. Information flows pass through infrastructure in which China is only a user, not an owner.

The dollar remains the world oxygen of value, and Anglo-American capital controls its breathing. China accumulates gold, but stores it where the assets of the world elite lie. The yuan tries to take on a global role, but receives this role only to the extent that it does not violate the financial architecture of the dollar. Britain in this mechanism plays the role of a “chief administrator,” providing transnational capital with services without which Chinese revenue remains unavailable for transformation into global wealth.

The Communist Party of China is not a subject of socialist transformation. It acts as a political administrator of the interests of those capitalist groups that have built Chinese labor into the global surplus-value chain. The CPC provides order, strike suppression, a low price of labor power, and guarantees for the investor. It has control over the working class. It has no control over capital. Capital, becoming transnational, tears the economy out from under national authority: political leaderships may change, but the rate of profit remains.

Britain, having lost the fleet of ships, preserved the fleet of capital. Its empire is no longer measured by territories and colonies. It is measured by the right of signature, management of settlements, the provision of trust. It does not need flags and gunboats, but tables of risk coefficients. This is what modern domination looks like: the body of production is located in China, but the nervous system of value is located in London.

Both powers — China and the United Kingdom — appear opposed. In reality, they are parts of one order. The national sovereignty of China is reduced to labor management. The financial sovereignty remains with those who own the world’s settlements. The flag mast may stand in Beijing. The rudder of the market remains in the hands of the City.

Therefore, the question of power today is determined not by the amounts of steel, containers, or foreign exchange reserves. It is determined by who owns surplus value and who manages its circulation. The Chinese working class creates surplus value that flows away to British rentiers. If the Party retains power over the laboring people, but gives power over value to world capital, it serves not socialism, but its opposite.

The conclusion is simple: the world is divided not into states, but into classes. China is not the owner of the world’s factory. It is the largest supplier of labor power into a system where the distribution of power is determined by the owners of capital. Resistance to this order is possible only where the consciousness of the international working class arises. Without it, China will remain a giant without a brain, and Britain — a brain without a body. And both will serve one master — world financial capital.

Today the coin indeed has two sides. On one side is minted the factory power of China. On the other — the financial coat of arms of the British Empire, rebuilt into a service apparatus of world capital. The coin rings loudly, because it is controlled by capital, not labor.

Imperialism remains the highest stage of capitalism precisely because it unites backwardness and modernity, the state banner and private interest, national labor and transnational profit. As long as this system exists, every new ton of steel and every new container of electronics will ring not in favor of those who produce them, but in favor of those who control their circulation.

However, the ring of the coin is not eternal. Where capital seeks to subordinate both China and Britain, the international working class begins to hear not the ring of profit, but the clanging of its own chains. And at that moment it becomes clear that the elimination of imperialism means not just a silenced sound. It means the return of value to those who create it.

While imperialism lives, the coin remains ringing. But together with its ringing, the law of its own demise continues to sound.

Editorial EasternPost

Publisher: The Eastern Post, London-Paris, United Kingdom-France, 2025.